Ta ta Terry

After hypnotherapy for stress and depression, Andy

spent a long time in the garden of his new house writing songs and poetry –

some good stuff came out, but it wasn’t helping him. He simply couldn’t leave

the house for feeling that everybody would be looking at him – he was seriously

unhinged for a while.

More hypnotherapy helped as Andy slowly realised he

wasn’t going to be the next Peter Green or Syd Barrett, but the financial mess

of the cancelled tour meant Virgin had to bail them out – and new Virgin boss

Jeremy Lascelles effectively owned them. Andy was also highly aware that the

others had enjoyed touring – most notably Terry – and felt he owed them

something.

There was only one solution – write another hit

album. Andy had spent most of 1982 in his back garden barely operating at

mumbling point, but the emotional turmoil had set the creative juices flowing

again – just as the enforced break had thrown Colin into a writer’s block.

When, in 1983, the band entered the studio again Andy

was enthusing about a new batch of songs he had written, which summed up what –

in his opinion – life was all about. The new material was an even more radical

leap into the pastoral, eschewing much of the traditional pop-song standard

features. In particular, Andy wanted to get a rustic, tribal beat going – which

didn’t include much in the way of ‘real’ drums.

Terry Chambers was not happy – he’d lost the

opportunity to tour, his pregnant Australian girlfriend was homesick – and now,

to cap it all, Andy wanted him to play bongos and timbales! One day, while

working on the opening track, Terry could not get the drum pattern Andy wanted

and tensions were rising.

In a moment, Terry put down his sticks, picked up his

keys and fags and said, “I’m off then chaps, so err, see ya,” and he was gone,

cymbals still swinging on their stands. Within six months, Terry Chambers had

moved to Australia with his new wife and baby and quit music altogether. Once

again, it’s nice to note that Terry has carved out a successful career in

Australia – where his son Kai is now the resident musician in the family – and

on his infrequent visits home, the old lads normally meet up for a drink or

two.

Meanwhile, there were drums (of sorts) to be played

and Pete Phipps, previously of (wait for it) The Glitter Band, deputised and

proved to be a versatile and open-minded player, which was just what Andy

needed.

Down on the farm

However, a shock was waiting – the band were happy

with the album, the remixes had gone well (a rarity with Partridge involved)

and everything looked rosy. Then Virgin A&R man Jeremy Lascelles rejected

it, telling the boys to go away and write another one!

| The band was crestfallen – and a plan was hatched.

They wrote one new song, changed the running order of the rest and took it back

to Lascelles. “Great,” said Lascelles, “I knew you could do it.” The album was

called Mummer (right) after the ‘Mummers’ (or mimers) who used to tour mediaeval

England with biblical and passion plays.

Mummer starts with another opening belter. Beating

of Hearts is about the power of the human spirit – from the internal

metronome that wakes you each morning, to the ability to outlast guns, tanks

and bombers, your heart is the “loudest sound in this and every world you can

think of.”

|

|

Love on a Farmboys Wages was inspired by Andy’s father, who, once leaving the

Navy, got a job collecting milk churns. He would often take the young Andy with

him during summer holidays and although this was as close to being a farmer as

either Partridge would ever get, the image offered a romantic, Thomas Hardy

angle for another song on the perils of poverty. It helped that snippets of the

song were taken from his own life – especially the endless condescension of

Marianne’s parents, who thought their little girl had married beneath herself.

Me And The Wind is about the bittersweet feeling at the end of a relationship. Many

people subscribe to the theory that it was Andy writing about Terry’s departure

– Andy insists he had no such thoughts in mind when he wrote it.

However, Andy was also aware that he had written a

no-hit album (Love on a Farmboys Wages hit the dizzy heights of No. 50

and that was it) and penned what he thought was his retirement song to end the

album with a resounding thud. Funk Pop A

Roll lambasted the music industry (again) and in particular it’s habit of

compartmentalising artists and forcing a formulaic ‘product’ on an unwitting

public:

Funk pop a roll beats up my soul

Oozing like napalm from the speakers and grill of your radio

Into the mouths of babes

And across the backs of its willing slaves

Funk pop a roll consumes you whole

Gulping in your opium so copiously from a disco

Everything you eat is waste

But swallowing is easy when it has no taste

However, he was quick to acknowledge his own complicity in the

last verse:

Funk pop a roll the only goal

The music business is a hammer to keep

You pegs in your holes

But please don't listen to me

I've already been poisoned by this industry

The album ends with Andy shouting a

cheery “bye bye” on the song’s fade-out. He truly believed at the time it would

be his last effort.

There is much debate among the XTC faithful as to

whether Mummer is a weak link in the band's recorded history or a key ‘not so

missing’ link between the old XTC and the new. There’s no doubt it polarises

opinion amongst fans like no other (it’s the Marmite of the XTC canon). It’s

fair to say XTC's sixth album is a little trickier to get into, but all the

more rewarding for it.

Andy is in no doubt as to how he feels

about it: "Until early 1982, our work was like black-and-white TV. Mummer

was the first in full colour – bright sky blue."

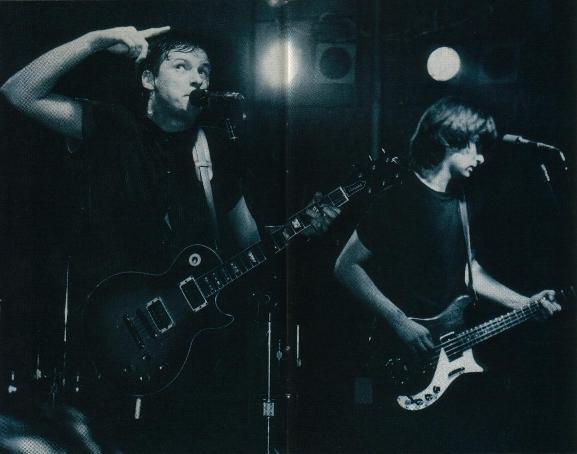

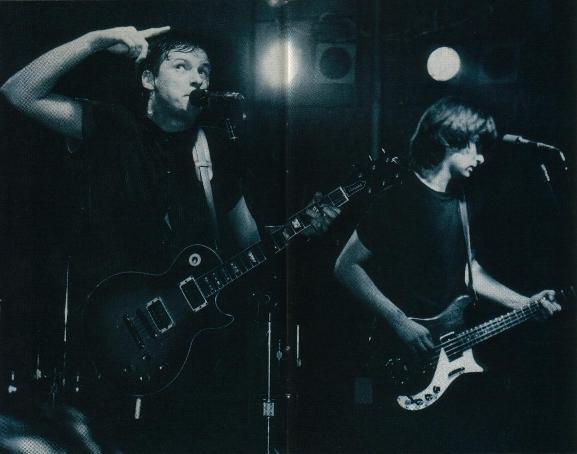

Moulding and Partridge, 1984 |

Express Delivery

Andy Partridge had often bemoaned that their

Swindonian origins made them the target of fashion bigots. He disliked the

oft-made comparisons with Talking Heads – not because of the music, but because

Talking Heads were the epitome of ‘New York cool’ and he wondered whether this

had as much to do with their success as Swindon had with XTC’s lack of it.

The next album showed a change of mood. Andy was already

annoyed at the lack of success of Mummer, which he felt was down to Virgin’s

apathy towards it and lack of promotion. This time he wasn’t going to back

down, he was going to shout out his pride at being English – and more

importantly, a yokel, as he thought Virgin saw him.

|

The resulting 1984’s The Big Express took an

eternity to record – getting through four producers and also witnessing the

bands split with their manager. It was, if anything, a slight return to their

rock roots – even if only via the pounding beats Pete Phipps layered over the

songs. In his spare time, Andy spent much of the recording process in his attic

– playing with his toy soldiers and dreaming about an idea for a spoof

psychedelic band.

The Big Express once again should have been the

mega-hit the band needed – but when you’re terminally unfashionable – well, you

know the story. Eleven stunning tracks, with nary a dud in sight. For anyone

who loves pop music, in its truest sense, here were tunes to kill for. If you

ask me, The Beatles were rarely this good.

The Big Express starts with Wake Up, Colin’s

three chord wonder – although no-one expected him to layer them on top of each

other in this ode to his early days of marriage, when he and his missus were so

often ‘at it’ he started to miss work through exhaustion!

Released as the first single, it

obviously bombed, but Andy was, nevertheless, impressed: “Colin arrived on my

doorstep one day with a grubby cassette in his mitts to announce ‘I've got a new song’. I was excited,

so we went into my front room and put it on straight away. I fell in love with

those twin chopping guitars, snapping across each other like a pair of

quarrelsome Jack Russells. That ‘missing beat’ drum rhythm was great too. I

love the competition, nothing makes me write faster than Colin appearing with a

new tune, it's always inspirational.”

|

The second single release, All You Pretty Girls, was Andy’s great lost sea-shanty. Hitting the

dizzy lows of No. 55 in the charts, it was written as a deliberately rose-tinted

view of what Andy’s father’s life in the navy might have been like if all the

accepted rumours were true:

Do

something for me, boys

If I should die at sea, boys

Write a little note, boys

Set it off afloat, saying

Bless you, bless you, all of you pretty girls

Village and city girls by the quayside

Bless you, bless you, all of you pretty girls

Watching and waiting by the sea

|

|

As well as the single releases, The Big Express is

choc-full of little gems, including The

Everyday Story of Smalltown, an obvious reference to the sanctity of

Swindonian life.

If

it's all the same to you, Mrs. Progress

Think I'll drink my Oxo up, and get away

It's not that you're repulsive to see

In your brand new catalogue nylon nightie

But you're too fast for little old me

Next you'll be telling me it's 1990

On a more sombre note,

Seagulls Screaming Kiss Her Kiss Her was

the first sign of the cracks in Andy’s marriage to Marianne. It was written

with reference to an American backing singer he had met while recording Mummer

– Erica Wexler – who made no secret of her affection for him. Although Andy had

resisted her charms, by this time she was always in his thoughts – and always

writing him letters, making Marianne all the more cold. It wasn’t the first

song he would write about Erica – and it isn’t the last we see of her.

The penultimate track, I Remember The Sun is one of Moulding’s finest moments, striking

the perfect nerve about the endless summers of childhood. Melting tarmac,

burning chaff, distant days when the sun always shone. It’s too perfect . . .

and all too true.

Around the time of the recording of The Big Express,

relations between the band and their manager, Ian Reid, fell apart completely.

Reid (“the G is silent,” Andy) was an ambitious ex-Army officer, who owned The

Affair club in Swindon where XTC played many early gigs, and talked the young

and naive band into signing him up as their manager, despite little previous

experience. To his credit, Reid got XTC signed up amongst the burgeoning punk

movement and, through his contacts, was able to keep them gigging constantly,

when constant gigging was the thing to do to be noticed.

However, after the debacle of the cancelled US tour,

Reid refused to contribute to covering any of the costs, which forced the band

into renegotiating their already punitive deal with Virgin. The result was,

that after seven decent-selling albums, a couple of hits and a loyal fan

support, XTC were still paupers and Reid was a rich man.

Furthermore, although English

Settlement had made a healthy profit, the band also received a huge unpaid

VAT bill for the time Ian Reid was in charge of their finances. On legal

advice, XTC sued Reid – who immediately counter-sued for unpaid commission on

royalties. As litigation ensued, Virgin were legally required to freeze royalty

and advance payments and divert publishing income into a frozen deposit

account.

Eventually, with the

case dragging on for years, XTC were forced to live on short term loans from

Virgin and PRS payments for airplay. Early in 1986, the band met with Virgin

for what was expected to be a routine album planning but, according to Andy,

"was more of a veiled threat that if we didn't listen to their advice and

sell more than 70,000 copies, we could find ourselves without a label."

The pressure was well

and truly back on.

The only positive

outcome was another track on The Big Express – I Bought Myself A Liarbird. A savage retort to the underhand

tactics and – as Andy saw them – lies and broken promises of Reid, it was so

damning that as part of the out-of-court settlement that eventually transpired

between the band and their manager, none of the band are allowed to mention its

existence, let alone perform it or allow the publishing of its lyrics. Of

course, you could just buy the album . . .

Part 4